Diagnosing Power Steering Problems

When trying to determine what is causing a problem in your power steering, keep this in mind. If the problem occurs only in one direction, the problem is probably in the box or rack. If the problem is in both directions, it is most likely the pump, dirty fluid or hoses. Be sure there are no kinks or obstructions in your power steering hoses and that they are the right inside diameter for the application.

Dirty Steering System

Before changing any single component of the steering system, inspect the cleanliness of your system. Dirty or black fluid can quickly ruin new steering components. If changing the box or rack, rub your finger on the inside of the reservoir. If it isn’t clean, you must flush the pump and hoses with clean fluid before installing new components.

Bleeding Power Steering

All power steering systems are designed to be self-bleeding, but sometimes they need a little help. After installing new components, fill the reservoir and let it sit for a few minutes. Raise the front end of the vehicle and turn the wheels back and forth slowly with the engine off to allow the steering box to draw fluid. Keep the reservoir full. When the fluid level stops dropping, start the vehicle and continue turning the wheels. When the fluid level remains constant the system is fully bled. Put cardboard under the front tires while testing your steering system. The cardboard will slide on the floor and prevent wearing flat spots on the tires from excessive turning of the wheels while not moving.

IMPORTANT NOTE: All GM power steering pumps generate approximately 1,000 to 1,200 PSI of line pressure. This is compatible with GM steering boxes and GM rack and pinion units. If these pumps are used with a Mustang II rack & pinion, the steering will feel too sensitive on the highway. This can be corrected by adjusting the pumps flow control valve to generate the proper pressure for the Mustang rack.

Splines and Irregular Shapes… The Strongest Method

Detroit uses irregularly shaped shafts such as spined or a “Double D” configuration and inserts them into a similarly shaped hole with practically no play and then secures them by staking or clamping. Since steering failures are practically unheard of in modern production cars, one should strongly consider this method as having significant merit.

Borgeson offers splined shafts and joints which give the option of easy disassembly when repairs on the vehicle become necessary. Another advantage is the ability to rotate the shaft in relation to the u-joint in small increments. This makes it easier to position the u-joints in the correct relationship to each other.

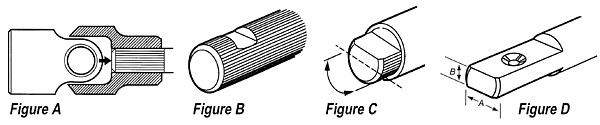

A flat should be filed on the splined shaft where the set screw will clamp (figure B). This will prevent damage to the spline and allow for easier disassembly. Always lock the set screw with a lock nut, Loc-Tite or similar product. The shaft must be flush with the inside of the yoke (figure A), not so short that it sacrifices strength or so long that it interferes with the center workings of the joint.

To determine the spline size of a component, measure the outside diameter and count the number of splines. If there is a flat spot on the shaft and some of the splines are missing, (figure C) count halfway around where there are splines and double that number. We need to know how many teeth are in a theoretical full circle. If you have something unusual or you’re unsure about measuring the spline, make an impression of it in clay and send it to us.

A “double D” (figure D) shaft has two large flat spots machined on the shaft that correspond to two flats in the female end of the u-joint. The disadvantage of this style is the lack of adjustability because the shaft can only be rotated 180°. The double D shaft should have a “dimple” machined on the shaft for the set screw to clamp to (figure D).

Count the number of splines of half of the circumference and double that number for total.